Climate change and the “tragedy of the commons”

“The tragedy of the commons” is familiar to anyone who has taken a course in environmental studies. We imagine a “commons”, say a shared green where villagers pasture their cows. The quality of the resource inevitably declines as villagers put more and more cows out to pasture on the green, leading to overgrazing. They do this because each villager obtains all the gain from having one more cow to milk, whereas the cost of the degradation of the pasture is shared among all the villagers, so the cost to each villager is the total loss divided by the (presumably large) number of villagers.

Recently TTOTC has been deployed to explain global warming. Superficially, at least, this makes sense. Earth’s climate is, indeed, a global commons. Nearly everyone suffers if the climate is degraded. And the benefits one derives from actions that contribute to such degradation accrue to individuals. If I drive my car to the store I, and I alone, benefit, from the convenience of getting my groceries home quickly and easily, while the carbon dioxide my car emits contributes to the degradation of the climate that is shared by everyone.

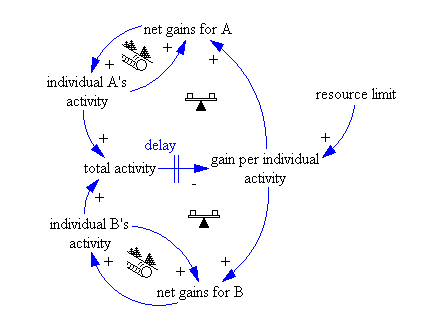

Yet there is a critical way in which TTOTC does not apply to climate change, at least not the usual metaphors of a village green or a fishery. Consider, first, the village green. If I choose not to pasture another cow on the green, the grass will be a little better, and this will encourage others to pasture more cows. Similarly, in a fishery, if I keep my boat in port, others will have a slightly better catch, and they will keep there boats at sea longer to avail themselves of it. In both cases, my restraint in choosing not to overexploit a resource has no beneficial effect, since others quickly snap up whatever resource I leave “on the table.”

But this is not what happens in global warming. In no way do my efforts to reduce emissions of heat trapping gases encourage or incentivize others to emit more. Simply put, when I reduce my emissions, the atmospheric burden of heat trapping is reduced, however slightly, leading to reduced (again, if slightly) climate change, resulting in reduced damage to the planet and reduced human misery. In short, any reduction I make in my emissions is an unalloyed good.

This is a striking and important way that climate change differs from the standard examples of TTOTC, yet it does not seem to be widely appreciated. On the contrary, whenever there is discussion of a national policy (in the US) to reduce emissions, someone is sure to say “but what about the Chinese?” As if, somehow, reduced emissions of heat trapping gases by the US will incentivize the Chinese to pollute more. In fact, the opposite is likely the case. As we emit less, this leads to technological developments, such as in clean energy, that enable reduced emissions everywhere. And US leadership in reducing emissions can produce social and geopolitical pressures that encourage others to pollute less. But even without such “knock-on” benefits, there is the simple fact that a ton of CO2 we do not emit – be it from our town, our university, our state or our nation – is a ton of CO2 that is not in the atmosphere wreaking current and future climate mayhem.

This is a hugely optimistic understanding, It tells us that efforts to reduce emissions on any level – personal, campus, community, state – are intrinsically beneficial and worthwhile, and we should go forward with them, whether or not there is effective climate leadership at the national and global levels. An example is what is happening right now in my State of North Carolina, where, under the aegis of Governor Roy Cooper’s Executive Order 80.we are in the midst of the bottoms-up, stakeholder (who, on Earth, is not a stakeholder in the climate?) driven development of a clean energy plan for North Carolina. As a participant in this process, I am encouraged by the commitment of participants, from many sectors, including the energy sector, to set North Carolina on the path to greatly reduced emissions of heat trapping gases.

One can imagine this process is being repeated by thousands or tens of thousands of entities, each one exerting its agency to reduce the damage global warming is wreaking on our planet. While it remains to be seen if this will work, or at least work well enough to avert a global climate catastrophe, it is only because the contributions made by each entity to reduce emissions are truly additive that it stands any chance of working. Unlike in a village green or a fishery TTOTC does not apply, and there is no inexorable dynamic that drives our climate to a tragic end.